LEMUEL GULLIVER - Although Gulliver is a bold adventurer who visits a multitude of strange lands, it is difficult to regard him as truly heroic. Even well before his slide into misanthropy at the end of the book, he simply does not show the stuff of which grand heroes are made. He is not cowardly—on the contrary, he undergoes the unnerving experiences of nearly being devoured by a giant rat, taken captive by pirates, shipwrecked on faraway shores, sexually assaulted by an eleven-year-old girl, and shot in the face with poison arrows. Additionally, the isolation from humanity that he endures for sixteen years must be hard to bear, though Gulliver rarely talks about such matters. Yet despite the courage Gulliver shows throughout his voyages, his character lacks basic greatness. This impression could be due to the fact that he rarely shows his feelings, reveals his soul, or experiences great passions of any sort. But other literary adventurers, like Odysseus in Homer's Odyssey, seem heroic without being particularly open about their emotions. (...)

If you want to continue reading CLICK HERE

If you want to continue reading CLICK HERE

DEFOE VS SWIFT

The two great prose writers of the Age of Queen Anne stand out as representatives of two worlds, of two cultures in conflict: the last of the aristocrats and the herald of the middle class.

Here are just a few hints to reflect on the differences between them

DANIEL DEFOE

|

JONATHAN SWIFT

|

English

|

Irish

|

Liberal ( Whig)

|

Conservative (Tory)

|

Dissenter

|

Anglican

|

Optimistic

|

Pessimistic

|

Exalted the use of reason

|

Satirized the use of reason

|

Championed individualism

|

Condemned individualism

|

Realistic novels

|

Imaginary voyages

|

And now a closer look at SWIFT's GULLIVER'S TRAVELS

SATIRE

Gulliver’s Travels has been considered a satirical masterpiece. But what is SATIRE?

Satire has been practised in all periods of English Literature , from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Satire can be shocking and destructive in its exposure of weakness, vice and folly, but has the positive purpose of correcting and reforming, and contrasting the actual with an existing or desired ideal.

CLICK HERE TO DISCOVER MORE

UTOPIA VS REALITY

This contrast in GULLIVER’S TRAVELS takes different forms:

· In the first book the very small Lilliputians exemplify the meanness and pettiness of our world; The Lilliputians are cruel and treacherous, only great in their thirst for power;

· In the second book proportions are reversed. The gigantic size of the people of Brobdingnag allows Gulliver to see all the physical imperfections of man, as if seen through the lens of a microscope; on the other hand, they are wise and good and, after hearing Gulliver describe English civilization, conclude that it is barbarous;

· The voyage to Laputa in the third book, is a more direct satire of contemporary England. Swift satirizes modern philosophies and science, and their presumptuousness in claiming to be able to solve all mankind’s problems;

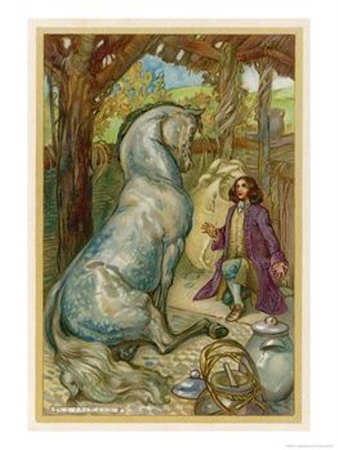

· In the last voyage, in the fourth book, Gulliver is faced with the degraded humanity of the Yahoos (which he recognizes as his own) and at the same time with the superior intelligence of the wise horses. Gulliver, a confused ordinary man, is caught in the middle; when the story ends, he no longer knows to which world he belongs.

INTERPRETATIONS OF GULLIVER’S TRAVELS

The book was a huge success when it was published, altough its venomous satire alienated late 18th and 19th centuries critical opinion: Swift was viewed as lonely and bitter man, disappointed by a world which had denied him success in the Church or in politics, and who had written his book in revenge. After his death it was mainly Part IV which which caused the strongest invective, as shown by the reaction of the 19th century novelist Thackeray, who considered Swift “a monster gibbering shrieks and gnashing imprecations against mankind – tearing down all shreds of modesty, past all sense of manliness and shame; filthy in word, filthy in thought, furious, raging, obscene”.

Even 20th century century readers have been shocked by Swift’s hatred of mankind, and continue the 18th century debate between defenders and critics, a debate that Swift’s might have liked, as implied by what he wrote to his friend Pope: “the chief end I propose to myself in all my labours is to vex the world rather than divert it”.

Swift offers no easy answers he has been alternatively defined a misanthrope and an idealist, a Tory and a radical, a misogynist and a supporter of women’s education; he did write with savage indignation, but we know that he was neither a lunatic nor a misanthrope, and was certinly moved by moral passion.

How seriously should we take Part IV, then ? Here the Houyhnhnms and the Yahoos are presented as the extremes of reason and passion: the Houyhnhnms have no “opinions”, no disputes, no special family affections, marriage being for them “one of the necessary actions of a rational being”; their life is without humour, doubt or passion. We wonder then how attractive this society can be, and if it could have had any appeal for Swift. The savage and disgusting Yahoos, on the other hand, who are the closest to the human species, are a condemnation of human beings: the Houyhnhnms represent an impossible and inhuman standard of perfection; “they may have all the reason, but the Yahoos have all the life (…) the clean skin of Houyhnhnms, in short, is stretched over a void”, as the critic F.R.Leavis beautifully summed up.

Is man a Yahoo then? The question is extremely difficult to answer. At the end of Part IV Gulliver is left suspended in a middle state, between angels and beasts, and Swift is determined to unsettle our mind, although the conclusion which he has led us to accept, that man is a Yahoo, is untenable and outrageous. Part IV is also difficult to interpret because the relation between Swift and Gulliver is never predictable, and we never know how much distance there is between them. At the end of the novel Gulliver shows very little self-understanding and his attitude is one of irreconcilable disgust for humanity, but we are not so sure about Swift: he might agree with his narrator the Houyhnhnms are “endowed by nature with a general disposition to all virtues” or might be attacking their cold rationalism behind Gulliver’s back. We close the novel wondering whether Swift satirises the dangerous illusion of man’s perfectability, or the idea that man is a rational animal, or whether he is more simply saying that man occupies a middle place between angels and beasts and partakes of the qualities of both, at his highest potential a little less than angel, and at his lowest little more than beast.

ROBINSON VS GULLIVER

origins

|

reasons for travelling

|

kind of journey

|

response to situations

|

writer’s aim

| |

ROBINSON

|

Middle class

|

For transgression and for money

|

To real places

|

Reacts positively

|

To exalt the ideals of English 18th century society

|

GULLIVER

|

Middle class

|

To seek profits

|

fantastic

|

Finds himself displaced

|

To use Gulliver as a mask behind which his criticism can be easily delivered

|

-+Jonathan+Swift,+Arthur+Pober,+Scott+McKowen-+Books_1221793524289.jpeg)

Thank you Maria..

ReplyDeleteThanks alot

ReplyDeleteThanks a lot!

ReplyDeleteUseful facts, thanks

ReplyDelete